From 2 to 7 February 2025, we organised a winter school for (our) PhDs: a one week course that was all about transdisciplinary research in the context of the transition to more ecology-based agriculture. A group of 32 motivated young scientist got together to dive into the topic of transition in (Dutch) agriculture, bringing their own specific disciplines to the table. How can they work together? And what is their role as a scientist in the transition?

We gave them a full programme of lectures in the mornings, group work on case studies in the afternoon, an excursion, and presentation from farmers. They talked about about how they run their farm, trying to move towards a future proof business.

Monday: Introduction to the context of the transition in agriculture

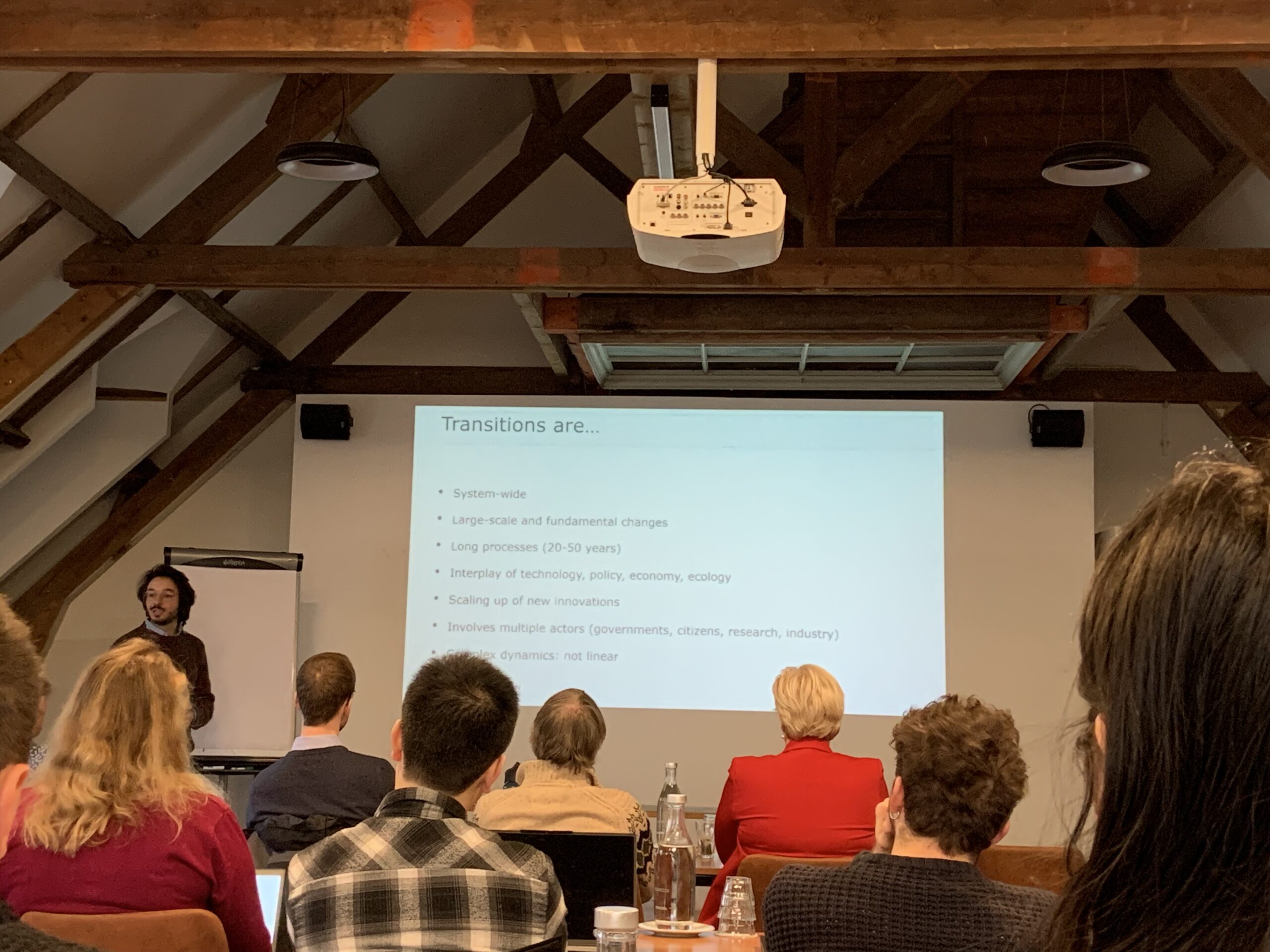

After an informal game of bingo to get to know each other on Sunday night, we kicked off on Monday with Kristiaan Kok, Dirk van Apeldoorn and Jeroen Candel. They introduced what transitions are, why we need one in agriculture and how history, politics and current events shape the (European) agricultural sector. Kris explained about transitions: what are they? He used the X-curve and Multi Level Perspective model for this. Dirk showed history of how agriculture in the Netherlands developed since 1900, including the green revolution, and start of heavy reliance on chemicals.

Jeroen Candel (WUR) introduced how European and Dutch politics played a role as well. With the Farm to Fork strategy being taken off the table by a more conservative political wind in Europe, but also events like the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine that make the EU shift its priorities. Closer to home, in the Netherlands, the same more conservative, right-wing wind rose to power. The election of the BBB has created eroding environmental leadership, but also the questioning of science, for example when it comes to the nitrogen crisis.

The lectures were followed by Mellany Klompe, who spoke about the farm she runs with her husband in de Hoeksche Waard. She explained what practices they have changed to make their farm more sustainable, in order for their children to be able to continue with the farm. “Game changer for us was a hiking trip to Nepal. We felt so stupid. They we’re doing it differently, we wanted to start with working with nature.”

Mellany’s farm is B Corp certified. “B Corp, only certificate that works for us so far. To show we do it differently.” They wanted to integrate nature’s rules in their farm, but the road is not always easy. “We tested and failed and paid lots of learning money, but by failure you learn. More than from success,” says Mellany.

She also admits that regenerative farming takes time, “But we don’t have it. Less and less people are working on farms, with more hectares to work.” To solve this, Mellany and her husband introduced strip cropping and a wider rotation, so more diversity in space and time. Including saying goodbye to sugar beets, that require very large machinery that destroys the soil. “Even if this means we had to decrease our profit.” The farm also uses compost tea and biofertilizer, no till, and everything is aimed at increasing the soil organic matter. This is why they aim to keep the soil covered with plants 365 days a year. “We like to think 100 years ahead,” says Mellany, “So our children have a head start when they take over the farm.”

In the afternoon, it was time to roll up our sleeves. The participants were divided into groups and each group was given a case study, loosely based on an existing farm. Their assignment: turn this farm into a future-proof and sustainable business, taking into account current practices, wishes of the farmer and the physical environment in which the farm is located. The groups could immediately sink their teeth into the basics: what crops does the farm grow? They made a rotation and thought about which crops are good for the soil and the earning model.

Tuesday: Crop interactions and technology

Tuesday was kicked off by bulb grower John Huiberts from Huiberts Biologische Bloembollen. He grows organic flowerbulbs in North-Holland. Of the 65 ha organic bulbs in the Netherlands, 40 are Huiberts’. John also focuses on a healthy soil and recognises the challenge of patience. “When you change your practices, you need patience. That was the hardest for me.” He explains how he gave himself five years to make the transition to organic. “The weeds were terrible, we almost stopped” he explained. “But just before the deadline, things started to settle down, so we pushed through."

John’s farm includes flowering field margins for natural enemies for aphids, but he also grows a mixture of fava beans and rye. “A good combination for structure in the soil and nitrogen fixation,” according to John. He also uses the faba beans to make compost. “We are always looking to feed the soil, not the plants.” Furthermore, John focuses a lot on green manure and he uses nettles to ferment and to spray over his crops in the form of nettle tea. He got the idea from vegetable gardeners. “If they do it, why shouldn’t I?” The nettles come from other farms, who are glad to be rid of them.

John is always looking for solutions that can help in conventional agriculture and he wants to spread the practices to the other 27.000 ha of bulbs in the Netherlands. “That is why I’m is happy to announce that the farm will be taken over by three young people, so my wife and I can retire and leave the farm in good hands.” First stop: a trip to Kazakhstan to see how tulips have been growing there for centuries.

After John’s intro, Marjolein Derks, Marius Monen and Niels Anten took the floor to give a lecture about the role of technology in the agricultural transition. First, Niels talked about how monocultures became the most efficient and therefore profitable way of farming. This meant more money for developing technology for it, creating ever more profit for monocultures. “People believe in a negative correlation between crop diversity and net income, but does this trade-off always exist? Can we change the lock-in? Can we make ecology leading instead of farmers following technological development?” He also posed the question of technology saving ecological farming, but can it do so without increasing inequality between farmers who can and cannot afford technologies? He concluded by stating that the resource use efficiency on the farm should also include the enthusiasm of the farmers, “They should be happy.”

Marius took over by diving deeper into technology, and more specifically, robotisation. He introduced the ‘window of viability’, the balance between diversity and sustainability. His main question: how can we use technology or robots to make systems more diverse? In his view, highly diverse landscapes are possible with the help of robots, as labour is very expensive and hard to come by in western Europe. He is not afraid that humans will completely become obsolete. “The robot is like a waiter. It can help you and serve you, but you need to instruct it to do the right things.”

Marjolein introduced the concepts of technology design. “A design is a function that converts something. It has constraints and requirements and designing something means finding solutions for this. The last step is to evaluate your solutions. Do they fit your needs?”

To stimulate the discussion, Marjolein also posed a question. “Marius and Niels are focusing on food production. But what else are we producing? You could integrate eco system services in your design, instead of keeping them outside of the equation.”

The last part of the morning was spent on getting to know each other better. All PhDs had speed dates to learn more about each other’s research.

Excursion to Loverendale Ter Linde

In the afternoon we visited Loverendale Ter Linde for a tour of the farm. It’s a mixed farm with orchards, cattle, and some arable fields. Because farmer Tim always dreamed of being a baker, he now not only has a bakery on the farm, but also recently bought a mill to mill his own cereals. We also got a tour of the storage and processing facilities, farm shop and playground. To finish off, Tim and his bakery team also fed us delicious pizza and desert!

Wednesday: Soil biology, business models, and regional scale

On Wednesday, Arjen van Buuren talked about the three organic farms that he manages with his wife Winny. “Soil biology is our most valuable capital,” explained Arjen. He was trained as a vegetable breeder, but he was always fascinated by nature. After a few years in Ireland, he was offered to manage a farm of Natuurmonumenten and now he and Winny are the leading example of how to farm in an extensive way, selling in the short chain. They produce mostly cereals and leave the weeds, since they can clean the products afterwards very well. The flower from their fields has enough protein to be used by bakers in the area. They ask higher prices, but in the short chain, their customers are willing to pay those prices, as they know what Arjen and Winny do for biodiversity and the landscape. Their mission is a healthy soil and a good earning model for farmers. “I want to work with nature, not place myself above it. Be humble. We need to understand how biology works,” concludes Arjen.

Following Arjen’s plea for more focus on soil life, was Marie Zwetsloot, who talked about the inhabitants of the soil and how they contribute to a healthy ecosystem. She showed us who inhabits the soil – soil biota – and how they are intertwined in the soil food web. Most of the organisms live on litter, compost, manure (dead material) instead of living stuff, as the species above ground do. Which organisms are present, tells you something about the others that are there. “If you find a centipede, you know the lower trophic levels are also there. Since it would not be there without food.” Marie concludes with saying that the nutrient cycle in the soil is crucial to crops.

For farmers, not only soil is important, but also their monetary revenue. Therefore, Duygu Keskin from TU Eindhoven talked about business models. “A business model is a conceptual framework of creating, delivering and capturing value,” she explained. “For value creation, you need activities, partners, and resources. To deliver that value, you need to know your customer segments, the channels through which you sell, and build customer relationships.”

She also described several types of business models that farmers can use. For example: Direct to consumer models, such as practiced when there is a shop on the farm; a model in which the farm sells food parcels, for example through CSA (community supported agriculture), or a local food business partnership model. In which the farmers form a cooperative in which they work together.

To finish of the morning sessions, Argyris Kanellopoulos (WUR) gave a crash course on building bioeconomic models. “You can use those models for optimising decision making,” he explained. “However, in practice you will almost never find the theoretical optimum that the model provides.” The model can for example be used to calculate the trade-off between biodiversity and revenue for the farmer. The curve of the model gives you a revenue (euros) for every score of biodiversity. This way, you could optimise the revenue, keeping into account preferences of for example consumers, diets, culture, and so forth. “The goal is to look for performance indicators and calculate trade-offs, so you can calculate the best biodiversity outcome for a specific income for example.”

During the afternoon, we delved deeper into the value of the farms that the participants designed on Monday. PJ Beers (HAS Green Academy) introduced thinking about value propositions and how farms can monetize all the ecosystem functions that they produce. What needs to change in the system and who should form coalitions to achieve systems change? The participants worked this out for the farms of the case studies that they had started to develop on Monday.

Thursday: Biodiversity and society

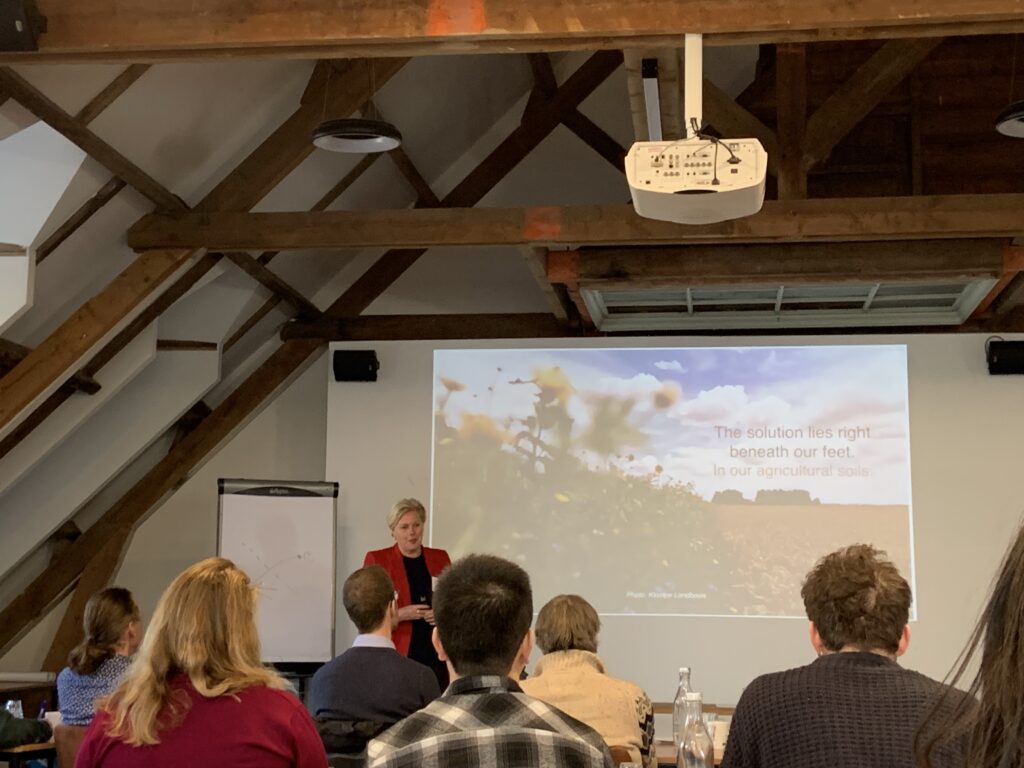

On Thursday, we were joined by Louise Vet, who has an impressive resume when it comes to getting involved in the societal debate about biodiversity restoration. She gave a flaming talk about using your science to inform society on how to bend the curve of biodiversity loss. She showed all sorts of graphs, but also warned us that you have to speak the language of your audience to get your message across.

She talked about how society should pay for ecosystem functions. “Like we pay for roads which only have one function and we do pay from public money, so why not pay for natural systems that provide a multitude of positive services to people and nature, such as clean water, clean air and biodiversity?”

Erik Poelman (WUR) followed Louise with a talk on what is biodiversity actually? Can we agree on that as scientist, so we get our message across? “The trouble is, that we forgot what biodiversity levels were like before. Young generations have no frame of reference to compare, for example, the insect populations to. For me, biodiversity is the interaction between species. We as humans influence many filters that determine biodiversity locally. We have a big influence, so we can also use that for good.”

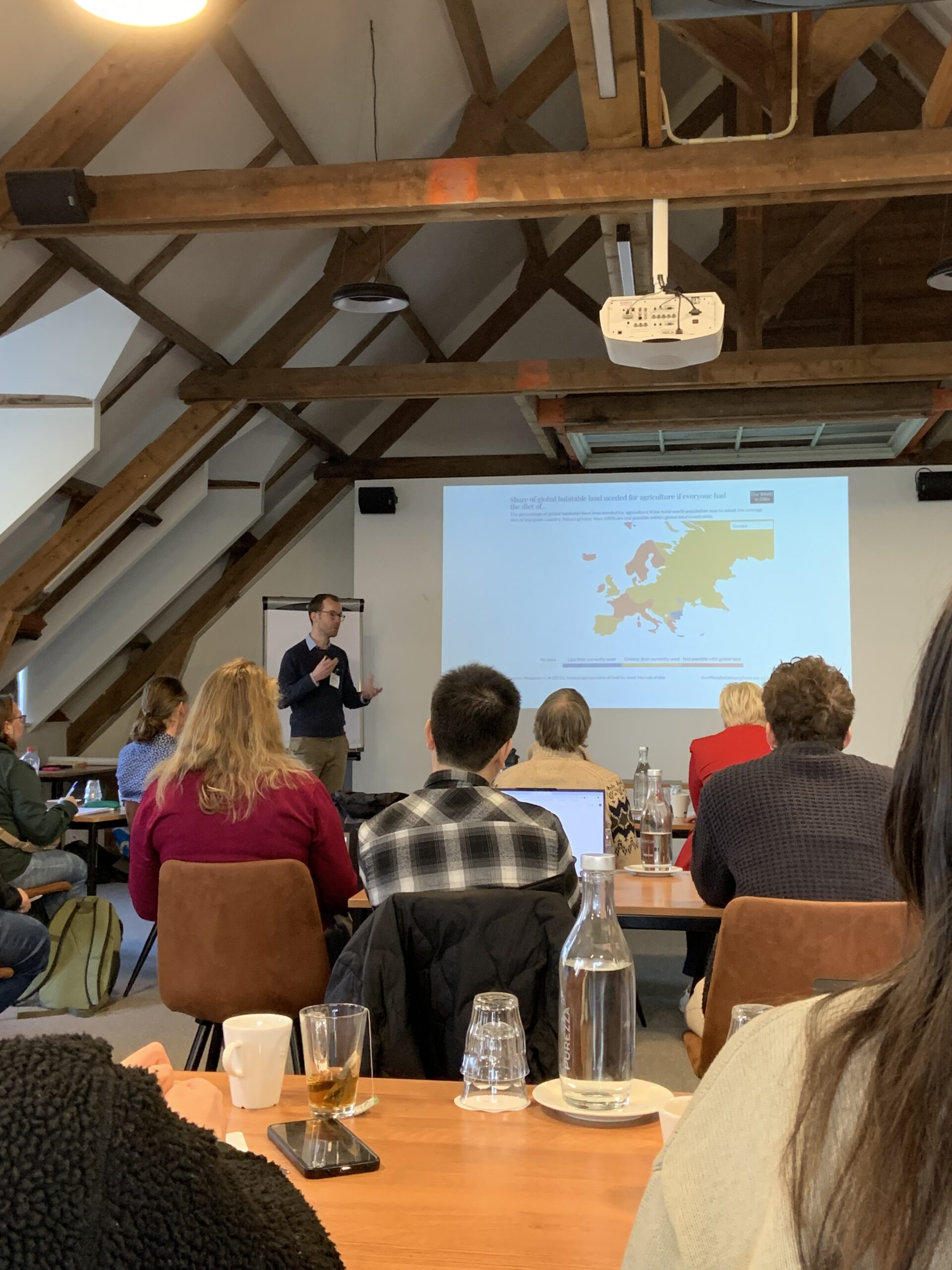

Bep Schrammeijer (VU, Athena Institute) then zoomed out to the biocultural level. What do landscapes mean to us and how does the landscape shape how we eat? But also, how does what we eat influence the landscape?

By the end of the morning, Joost van Strien, farmer in Flevoland, took the floor. His biodynamic farm in Flevoland is still evolving. After transitioning to organic about 25 years ago, and later moving towards biodynamic, he still isn’t done innovating. He has now added a food forest at the heart of his farm and has shifted to vegan fertilisation. He also invites guests to stay on his farm in summer on a little camping, that they can stay at for free for doing 6 hours of work on the farm every day. “It’s a lot of fun,” says Joost.

When asked about reactions from other farmers, Joost explains that many are skeptical of the way he runs his farm. “But they usually change their opinion when they visit the farm and stay there for a couple of hours. They have more understanding.”

On Thursday afternoon, the participants finished the designs of their farms by ‘future proofing’ them. What if the political and economic landscape would change? What would that mean for your farm? All groups got a specific scenario and did and impact assessment, guided by Bep.

Friday: Presenting the future farm designs

On Friday it was time to present all the farms that the groups envisioned. In a carrousel they went along the tables to see what their peers came up with and to ask questions. It was a lively session with every group having taken a different angle to approach making their farm more sustainable.

Lastly, we reflected on the week. Positive comments were made about the safety in the group to speak out, which young researchers might not always feel comfortable with. “In this group, you don’t have to fear your position. Senior researchers should protect us, so we feel comfortable speaking out in other settings as well.”

We also asked again about what the participants think is their role as a scientist. Many of them didn’t change their position compared to the beginning of the week. They were already convinced at the start of the course that they could take a stance in the public debate and help spread the importance of transition in agriculture through their research. However, many saw new opportunities in collaboration, but also a need for good communication strategies arose. “How will I communicate to the public and not just publish scientific papers?” mentioned one of the participants. We will work on this within CropMix in the second half of our programme.

In conclusion, the participants enjoyed the winter school and were happy to have gained knowledge on what other disciplines are doing and how their results could fit together. Working together on semi real life case studies was a hands-on way to practice these collaboration skills. We will probably show the designs of the future farms with the CropMix consortium, especially the farmer, to get their feedback on the ideas.

We look back on a very fruitful and interesting week. Thank you everyone who contributed, with special thanks to Thijmen and Frank for supporting the programme with feedback and games!